Object of Play

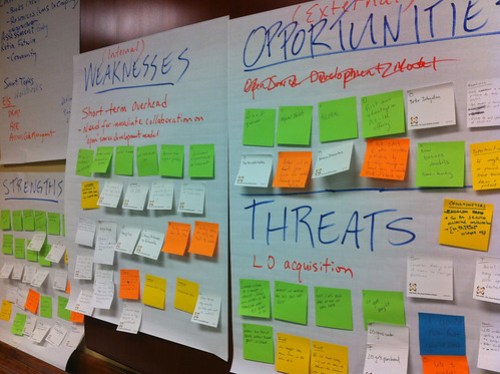

In business, it can be easier to have certainty around what we want, but more difficult to understand what’s impeding us in getting it. The SWOT Analysis is a long-standing technique of looking at what we have going for us with respect to a desired end state, as well as what we could improve on. It gives us an opportunity to gauge approaching opportunities and dangers, and assess the seriousness of the conditions that affect our future. When we understand those conditions, we can influence what comes next. So, if you need to evaluate your organization or team’s current likelihood of success relative to an objective.

Number of Players: 5–20

Duration of Play: 1–2 hours

How to Play

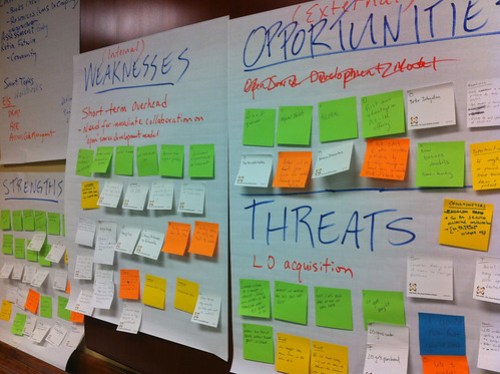

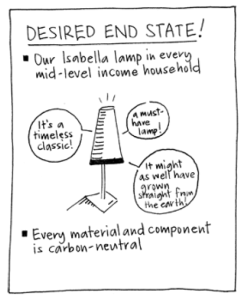

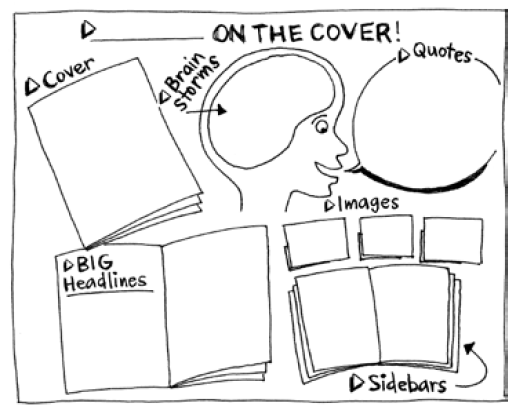

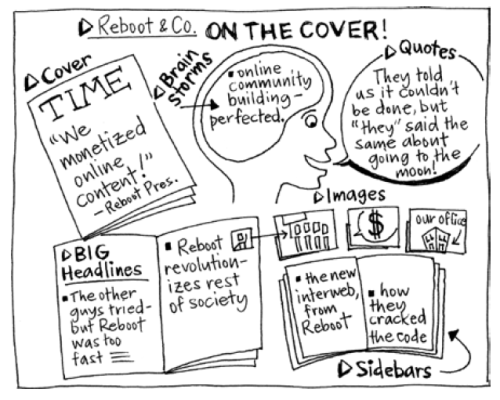

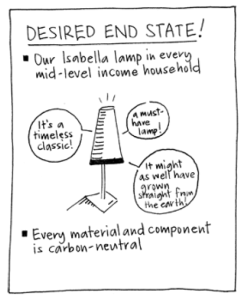

1. Before the meeting, write the phrase “Desired End State” and draw a picture of what it might look like on a piece of flip-chart paper.

2. Create a separate four-square quadrant using four sheets of flip-chart paper. If you think the complexity of the discussion and the number of players warrants more quadrants, create as many as you’d like.

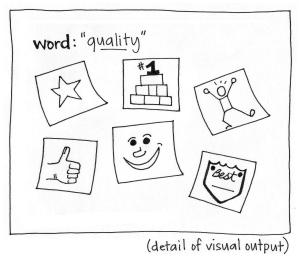

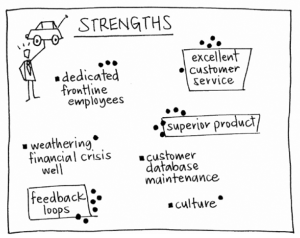

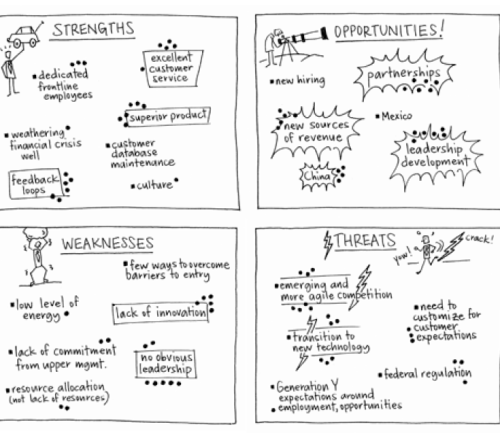

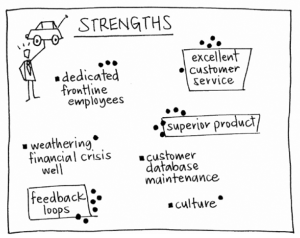

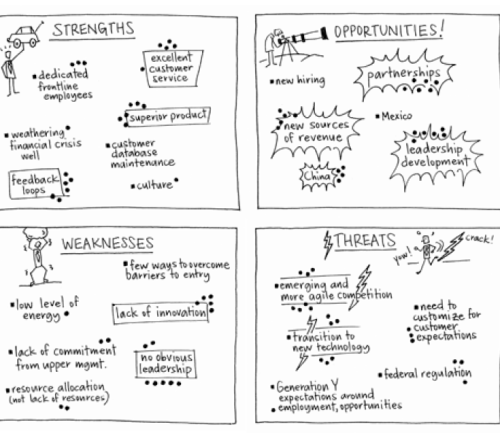

3. At the top left of the quadrant, write the word “STRENGTHS” and draw a picture depicting that concept. For example, for “STRENGTHS” you might draw a simple picture of someone holding up a car with one hand. (Yes, you’re allowed to exaggerate.) Ask the players to take 5–10 minutes and quietly generate ideas about strengths they have with respect to the desired end state and write them on sticky notes, one idea per sticky note.

4. At the bottom left of the quadrant, write the word “WEAKNESSES” and draw a picture depicting that concept. Ask the players again to take 5–10 minutes to quietly generate ideas about weaknesses around the desired end state and write them on sticky notes.

5. At the top right of the quadrant, write the word “OPPORTUNITIES” and draw a picture. Ask the players to take 5–10 minutes to write ideas about opportunities on sticky notes.

6. At the bottom right of the quadrant, write the word “THREATS” and draw a picture depicting that concept. Ask the players to use this last set of 5–10 minutes to generate ideas about perceived threats and write them on sticky notes.

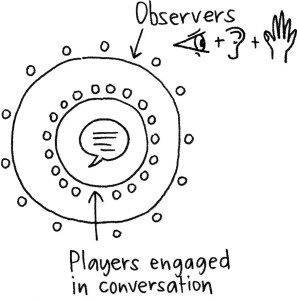

7. When you sense a lull in sticky-note generation, gather all of the sticky notes and post them on a flat surface that is near the quadrant and is viewable by the players. Be sure to keep the sticky notes in their original groups of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

8. Start with the STRENGTHS group of sticky notes and, with the players’ collaboration, sort the ideas based on their affinity to other ideas. For example, if they produced three sticky notes that say “good sharing of information,” “information transparency,” and “people willing to share data,” cluster those ideas together. Create multiple clusters until you have clustered the majority of the sticky notes. Place outliers separate from the clusters but still in playing range. (At this stage, it’s important to note that if you have a group with five players or less, you can eliminate the sticky-note clustering process and simply write and draw their responses for each category as the players verbalize them. After you’ve gone through each section of the quadrant, players can dot vote.) Repeat the clustering and sorting process for the other categories in this order: WEAKNESSES, OPPORTUNITIES, and finally, THREATS.

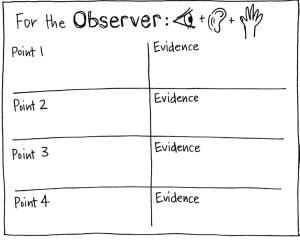

9. After the sorting and clustering is complete, start a group conversation to create a broad category for each smaller cluster. For example, a category for the cluster from step 8 might be “communication”. As the group makes suggestions and finds agreement on categories, write those categories in the appropriate quadrant.

10. When the players feel comfortable with the categories, ask them to approach the quadrant and dot vote next to two or three categories in each square, indicating that they believe those to be the most relevant for that section. Circle or highlight the information that got the most votes and make a note of it with the group.

11. Summarize the overall findings in conversation with the players and ask them to discuss the implications around the desired end state. Engage the group in a creative exercise wherein they evaluate weaknesses and threats positively, as though their presence is doing them a favor. Ask them thought-provoking

questions, like “What if your competition didn’t exist?” and “How does this threat have the potential to make the organization stronger?”

Optional activity: Lead the group in creating silly slogans for the desired end state. Let them be ridiculous: “Our lamps will light up the world.” The idea is to create humor and excitement around possibilities.

Strategy

The SWOT Analysis is at its best when the group is unabashed in its provision and analysis of content. The players are less likely to be shy about their strengths, but they may struggle to suggest weaknesses due to sensitivity to other players or to blind spots in their own thinking. Frame the notion of “weakness” to mean something that can be improved upon. Similarly, a “threat” is something that can act as a catalyst for performance improvement. Let the group know that the higher the quality of their contributions, the better they will be able to evaluate what’s on the horizon. You’ll have a good sense that

the game was successful when you hear the group thoughtfully consider the data and express insights they didn’t have before.

This game was inspired by Albert Humphrey’s traditional SWOT Analysis.