Object of Play

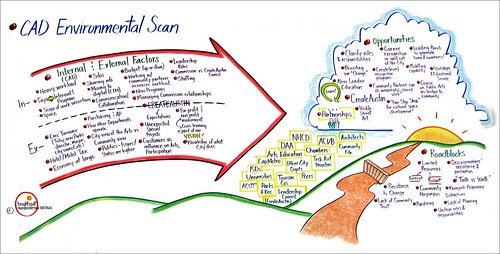

We don’t truly have a good grasp of a situation until we see it in a fuller context. The Context Map is designed to show us the external factors, trends, and forces at work surrounding an organization. Because once we have a systemic view of the external environment we’re in, we are better equipped to respond proactively to that landscape.

Number of Players: 5–25

Duration of Play: 45 minutes to 1.5 hours

How to Play

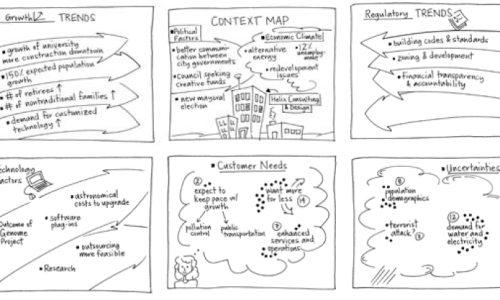

1. Hang six sheets of flip-chart paper on a wall in a two-row, three-column format.

2. On the top-middle sheet of flip-chart paper, draw a representation of the organization under discussion. It can be as simple as an image of your office building or an image of a globe to represent a global marketplace. Label the picture or scene.

3. On the same sheet of paper, above and to the left of the image, write the words “POLITICAL FACTORS”. Above and to the right, write the words “ECONOMIC CLIMATE”.

4. On the top-left sheet of flip-chart paper, draw several large arrows pointing to the right. Label this sheet “TRENDS”. Include a blank before the word TRENDS so that you can add a qualifier later.

5. On the top-right sheet of flip-chart paper, draw several large arrows pointing to the left. Label this sheet “TRENDS”. Again, include a blank before the word TRENDS so that you can add a qualifier later.

6. On the bottom-left sheet, draw large arrows pointing up and to the right. Label this sheet “TECHNOLOGY FACTORS”.

7. On the bottom-middle sheet, draw an image representing your client(s) and label the sheet “CUSTOMER NEEDS”.

8. On the bottom-right sheet, draw a thundercloud or a person with a question mark overhead and label this sheet “UNCERTAINTIES”.

9. Introduce the context map to the group. Explain that the goal of populating the map is to get a sense of the big picture in which your organization operates. Ask the players which category on the map they’d like to discuss first, other than TRENDS. Open up the category they select for comments and discussion. Write the comments they verbalize in the space created for that category.

10. Based on an indication from the group or your own sense of direction, move to another category and ask the group to offer ideas for that category. Continue populating the map with content until every category but TRENDS is filled in.

11. The two TRENDS categories can be qualified by the group, so take a quick poll to determine what kinds of trends the players would like to discuss. These could be online trends, demographic trends, growth trends, and so forth. As you help the players find agreement on qualifiers for the trends (conduct a dot vote or have them raise their hands if you need to), write those qualifiers in the blanks next to TRENDS. Then continue the process of requesting content and writing it in the appropriate space.

12. Summarize the overall findings with the group and ask for observations, insights, “aha’s,” and concerns about the context map.

Strategy

It’s up to the players to paint a picture of the environment in which they sit, but as the meeting leader, you can help them generate content by asking intelligent and thoughtprovoking questions. Conduct research or employee interviews before the meeting if you need to. The idea is to portray a context that is as rich and accurate as possible so that the players gain insight into their environment and can subsequently move proactively rather than reactively. The players can populate the categories other than TRENDS on the context map in any order, so note their starting point and pay attention to where they focus or generate the most content—both can indicate where their energy lies. But keep in mind that this activity is designed to generate a display of the external environment, not the internal one. So, if you notice that the discussion steers toward analyzing the internal context, guide them back to the outside world. There are other games for internal dynamics. The Context Map game should result in a holistic view of the external business landscape and show the group where they can focus their efforts to get strategic results.

This game is based on The Grove Consultants International’s Leader’s Guide to Accompany the Context Map Graphic Guide® ©1996–2010 The Grove.