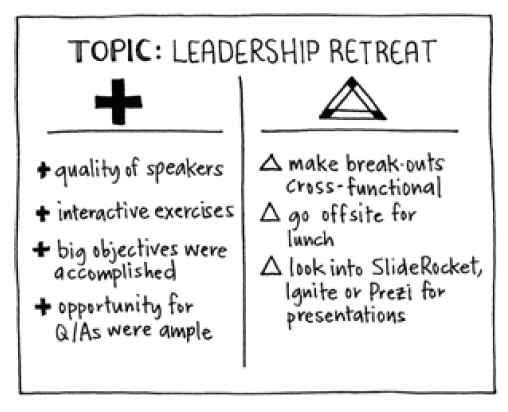

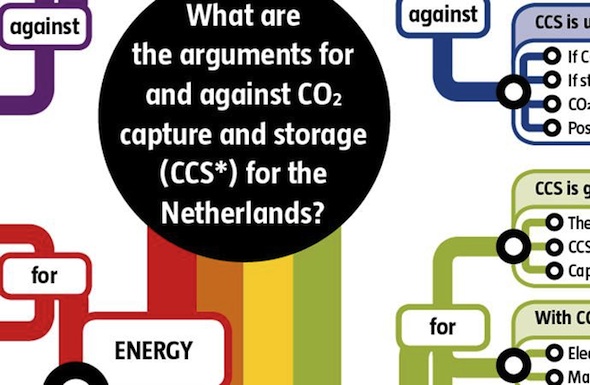

Pro/Con list, originally uploaded by dgray_xplane.

It’s rare that we can clearly establish the provenance of a Gamestorming approach, but it’s very nice when we can. The Pro and Con list is a good example: It was invented by Benjamin Franklin and described by him an a 1772 letter to Joseph Priestley. Here’s the description in Ben’s own words:

To Joseph Priestley

London, September 19, 1772

Dear Sir,

In the Affair of so much Importance to you, wherein you ask my Advice, I cannot for want of sufficient Premises, advise you what to determine, but if you please I will tell you how.

When these difficult Cases occur, they are difficult chiefly because while we have them under Consideration all the Reasons pro and con are not present to the Mind at the same time; but sometimes one Set present themselves, and at other times another, the first being out of Sight. Hence the various Purposes or Inclinations that alternately prevail, and the Uncertainty that perplexes us.

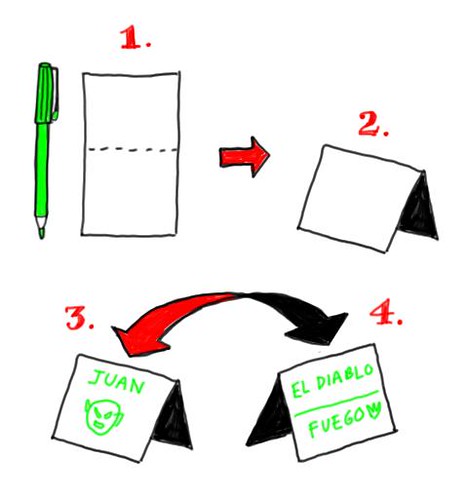

To get over this, my Way is, to divide half a Sheet of Paper by a Line into two Columns, writing over the one Pro, and over the other Con. Then during three or four Days Consideration I put down under the different Heads short Hints of the different Motives that at different Times occur to me for or against the Measure. When I have thus got them all together in one View, I endeavour to estimate their respective Weights; and where I find two, one on each side, that seem equal, I strike them both out: If I find a Reason pro equal to some two Reasons con, I strike out the three. If I judge some two Reasons con equal to some three Reasons pro, I strike out the five; and thus proceeding I find at length where the Ballance lies; and if after a Day or two of farther Consideration nothing new that is of Importance occurs on either side, I come to a Determination accordingly.

And tho’ the Weight of Reasons cannot be taken with the Precision of Algebraic Quantities, yet when each is thus considered separately and comparatively, and the whole lies before me, I think I can judge better, and am less likely to take a rash Step; and in fact I have found great Advantage from this kind of Equation, in what may be called Moral or Prudential Algebra.

Wishing sincerely that you may determine for the best, I am ever, my dear Friend,

Yours most affectionately

B. Franklin

Source: Mr. Franklin: A Selection from His Personal Letters. Contributors: Whitfield J. Bell Jr., editor, Franklin, author, Leonard W. Labaree, editor. Publisher: Yale University Press: New Haven, CT 1956.

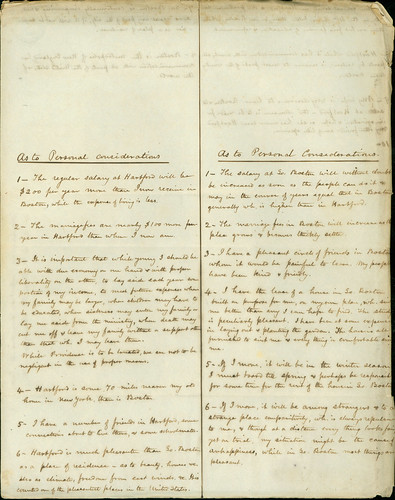

Note about the image: I couldn’t find an example of a Pro/Con list by Benjamin Franklin, but I found this image as part of a Connecticut Historical Society blog post about the Rev. William Patton, who made this Pro/Con list as he considered the relative merits of living in Boston vs. Hartford.

Image: Pros and cons of moving to Hartford, Rev. William W. Patton diaries and account book, 1835-1889, Ms 68129. CHS, Hartford, CT

Online Pro/Con List

Given Benjamin Franklin’s large and distributed social network, we’re pretty sure that he would have enjoyed playing this game with his friends and colleagues. And while dear Ben couldn’t engage his network very easily, we’re pretty sure that he’d be really happy to learn that you can engage your distributed team in an online Pro/Con game.

Given Benjamin Franklin’s large and distributed social network, we’re pretty sure that he would have enjoyed playing this game with his friends and colleagues. And while dear Ben couldn’t engage his network very easily, we’re pretty sure that he’d be really happy to learn that you can engage your distributed team in an online Pro/Con game.

Here is another image of the Pro/Con List Game. But this one is special – clicking on this image, will start an “instant play” game at www.innovationgames.com. In this game, there will be two icons that you can drag on your online Pro/Con List:

- Blue Pluses: Use these to capture Pros.

- Cons: Use these to capture Cons.

We’ve organized this game using multi-layered regions so that you can keep track of the importance of each item. There are High, Medium, and Low importance regions on the game board. As you’re moving items around, use these regions to help you keep track of the most important ideas.

Keep in mind that that this is a collaborative game. This means that you can invite other players to play. And when they drag something around – you’ll see it in real time!