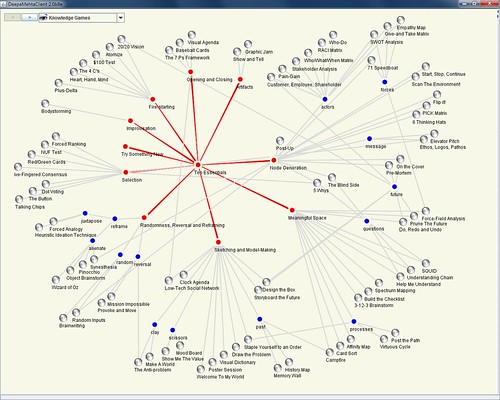

Great map by Matthias Melcher connecting the ten essentials with the list of games we are working on in the Gamestorming book.

Author: Dave Gray

Dave Gray’s Knowledge Games talk from the Interaction 10 conference

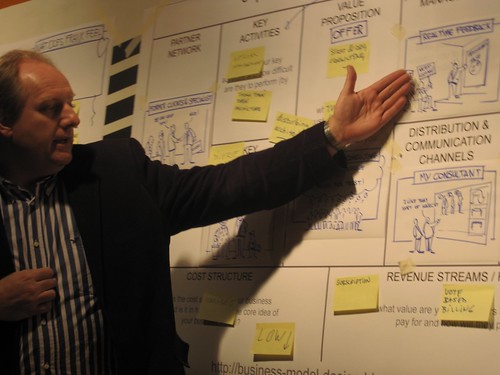

Mapping Business Models

Globalization and the emergence of digital business have changed the playing field for everyone. New business models can now rapidly disrupt an entire industry by changing the way value is delivered to customers (Look how Apple’s iTunes strategy disrupted the music industry, for example). The Business Model Canvas, developed by Alex Osterwalder, is a tool that you can use to examine and rethink your company’s business model. We are very pleased to announce a knowledge game for examining your business model and exploring alternatives, developed by Alex himself, and shared here for the first time. Thanks Alex!

Objective of Play: Visualize a business model idea or an organization’s current and/or future business model in order to create a shared understanding and highlight key drivers.

Number of Players: 1-6 (depending on the objective). Works well individually to quickly sketch out and think through a business model idea or an interesting business portrayed in the press. To map an organization’s existing and/or future business model you should work in groups. The more diverse the group of players (marketing, operations, finance, IT, etc.), the more accurate the picture of the business model will be.

Duration of Play: Anywhere between 15 minutes for individual play (napkin sketch of a business model idea), half a day (to map an organization’s existing business model), and two days (to develop a future business model or start-up business model, including business case).

Material required: Mapping business models works best when players work on a poster on the wall. To run a good session you will need:

- A very large print of a Business Canvas Poster. Ideally B0 format (1000mm × 1414mm or 39.4in × 55.7in)

- Tons of sticky notes (i.e. post-it® notes) of different colors

- Flip chart markers

- Camera to capture results

- The facilitator of the game might want to read an outline of the Business Model Canvas

How to Play: There are several games and variations you can play with the Business Model Canvas Poster. Here we describe the most basic game, which is the mapping of an organization’s existing business model (steps 1-3), it’s assessment (step 4), and the formulation of improved or potential new business models (step 5). The game can easily be adapted to the objectives of the players.

- A good way to start mapping your business model is by letting players begin to describe the different customer segments your organization serves. Players should put up different color sticky notes on the Canvas Poster for each type of segment. A group of customers represents a distinct segment if they have distinct needs and you offer them distinct value propositions (e.g. a newspapers serves readers and advertisers), or if they require different channels, customer relationships, or revenue streams.

- Subsequently, players should map out the value propositions your organization offers each customer segment. Players should use same color sticky notes for value propositions and customer segments that go together. If a value proposition targets two very different customer segments, the sticky note colors of both segments should be used.

- Then players should map out all the remaining building blocks of your organization’s business model with sticky notes. They should always try to use the colors of the related customer segment.

- When the players mapped out the whole business model they can start assessing its strength and weaknesses by putting up green (strength) and red (weakness) sticky notes alongside the strong and weak elements of the mapped business model. Alternatively, sticky notes marked with a “+” and “-” can be used rather than colors.

- Based on the visualization of your organization’s business model, which players mapped out in steps 1-4, they can now either try to improve the existing business model or generate totally new alternative business models. Ideally players use one or several additional Business Model Canvas Posters to map out improved business models or new alternatives.

Strategy: This is a very powerful game to start discussing an organization’s or a department’s business model. Because the players visualize the business model together they develop a very strong shared understanding of what their business model really is about. One would think the business model is clear to most people in an organization. Yet, it is not uncommon that mapping out an organization’s business model leads to very intense and deep discussions among the players to arrive at a consensus on what an organization’s business model really is.

The mapping of an organization’s existing business model, including its strengths and weaknesses, is an essential starting point to improve the current business model and/or develop new future business models. At the very least the game leads to a refined and shared understanding of an organization’s business model. At its best it helps players develop strategic directions for the future by outlining new and/or improved business models for the organization.

Variations: The Business Model Canvas Tool can be the basis of several other games, such as games to:

- generate a business model for a start-up organization

- develop a business model for a new product and/or service

- map out the business models of competitors, particularly insurgents with new business models

- map out and understand innovative business models in other industries as a source of inspiration

- communicate business models across an organization or to investors (e.g. for start-ups)

Elevator Pitch

Note: This approach is meant to be pretty flexible- other idea generating and prioritizing techniques may be substituted within the flow to suit the circumstances. Would like to hear how others approach this challenge. -James

Object of Play: What has been a time-proven exercise in product development applies equally well in developing any concept: writing the elevator pitch. Whether developing a service, a company-wide initiative, or just a good idea that merits spreading, a group will benefit from collaborating on what is- and isn’t– in the pitch.

Often this is the hardest thing to do in developing a new idea. An elevator pitch should be short and compelling description of the problem you’re solving, who you solve it for, and one key benefit that distinguishes it from its competitors. It must be unique, believable and important. The better and bigger the idea, the harder the pitch is to write.

Number of Players: Works as well individually as with a small working group

Duration of Play: Long- save at least 90 minutes for the entire exercise, and consider a short break after the initial idea generation is complete, before prioritizing and shaping the pitch itself. Small working groups will have an easier time coming to a final pitch; in some cases it may be necessary to assign one person follow-up accountability for the final wording after the large decisions have been made in the exercise.

How to Play:

Going through the exercise involves both a generating and forming phase. To setup the generating phase, write these questions in sequence on flipcharts:

- Who is the target customer?

- What is the customer need?

- What is the product name?

- What is its market category?

- What is its key benefit?

- Who or what is the competition?

- What is the product’s unique differentiator?

These will become the elements of the pitch. They are in a sequence that follows the formula: For (target customer) who has (customer need), (product name) is a (market category) that (one key benefit). Unlike (competition), the product (unique differentiator).

To finish the setup, explain the elements and their connection to each other.

The target customer and customer need are deceptively simple- any relatively good idea or product will likely have many potential customers and address a greater number of needs. In the generative phase, all of these are welcome ideas.

It is helpful to fix the product name in advance—this will help contain the scope of the conversation and focus the participants on “what” the pitch is about. It is not outside the realm of possibility, however, that there will be useful ideas generated in the course of exercise that relate to the product name, so it may be left open to interpretation.

The market category should be an easily understood description of the type of idea or product. It may sound like “employee portal” or “training program” or “peer-to-peer community.” The category gives an important frame of reference for the target customer, from which they will base comparisons and perceive value.

The key benefit will be one of the hardest areas for the group to shape in the final pitch. This is the single most compelling reason a target customer would buy into the idea. In an elevator pitch, there is no time to confuse the matter with multiple benefits- there can only be one memorable reason “why to buy.” However, in the generative phase, all ideas are welcome.

The competition and unique differentiator put the final punctuation on the pitch. Who or what will the target customer compare this idea to, and what’s unique to this idea? In some cases, the competition may literally be another firm or product. In other cases, it may be “the existing training program” or “the last time we tried a big change initiative.” The unique differentiator should be just that- unique to this idea or approach, in a way that distinguishes it in comparisons to the competition.

Step One: The Generating Phase

Once the elements are understood, participants brainstorm ideas on sticky notes that fit under each of the headers. At first, they should generate freely, without discussion or analysis, any ideas that fit into any of the categories. Using the Post-up technique, participants put their notes onto the flipcharts and share their ideas.

Next, the group may discuss areas where they have the most trouble on their current pitch. Do we know enough about the competition to claim a unique differentiator? Do we agree on a target customer? Is our market category defined, or are we trying to define something new? Where do we need to focus?

Before stepping into the formative phase, the group may use dot voting, affinity mapping or other method to prioritize and cull their ideas in each category.

Step Two: The Forming Phase

Following a discussion and reflection on the possible elements of a pitch, the group then has the task of “trying out” some possibilities.

This may be done by breaking into small groups, pairs, or as individuals, depending on the size of the larger group. Each given the task of writing out an elevator pitch, based on the ideas on the flipcharts.

After a set amount of time (15 minutes may be sufficient) the groups then reconvene and present their draft versions of the pitch. The group may choose to role play as a target customer while listening to the pitch, and comment or ask questions of the presenters.

The exercise is complete when there is a strong direction among the group on what the pitch should and should not contain. One potential outcome is the crafting of distinct pitches for different target customers; you may direct the groups to focus in this manner during the formative stage.

Strategy:

Don’t aim for final wording with a large group. It’s an achievement if you can get to that level of finish, but it’s not critical and can be shaped after the exercise. What is important is that the group decides on what is and is not a part of the pitch.

Role play is the fastest way to test a pitch. Assuming the role of a customer (or getting some real ones to participate in the exercise) will help filter out the jargon and empty terms that may interfere with a clear pitch. If the pitch is truly believable and compelling, participants should have no problem making it real with customers.

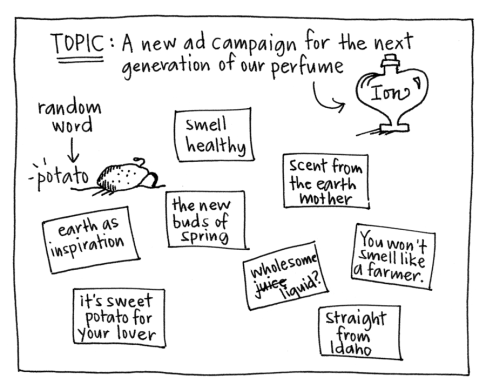

Random Inputs

NAME OF PLAY: Random Inputs

Object of Play: To generate random thinking and new ideas around any topic you choose.

# of Players: 5 – 10

Duration of Play: 30 minutes – 1 hour

How to Play:

- Before the meeting, generate a list of 50-75 random nouns. You can do this however you see fit, but try to ensure that the nouns are NOT contextually based on the players’ work.

- Write each word on an individual slip of paper and put all of them in a container you can draw from blindly.

- In a white space visible to all the players, write the topic of the play (ex. a new ad campaign) and give all players access to sticky notes – enough that they can generate potentially a dozen ideas per word.

- Tell the players that the goal of the game is to come up with ideas that are outside of the default thinking around the product or service. Tell them that the connections they make with the words can and should be expansive, even silly at first glance. Offer examples to clarify the kind of output you’re looking for.

- Draw the first word from your container and read it outloud to the players. Then draw a picture of it in the white space (even if you don’t really know how to.)

- Give everyone five minutes to quietly write on sticky notes any ideas they have related to the topic and inspired by the word.

- Ask the players to post all of their ideas in the white space.

- Repeat this process for the each word you pull from your container and keep going until you and the players feel like you’ve generated enough ideas to get traction on your topic.

Strategy: This play is powerful because the inputs are random, so it’s important that the list of words you generate before the meeting adheres to the principle of randomness as best it can. If you start compiling words that people associate with the topic, you’ll get ideas that the players have had many times before, which is the antithesis of the desired outcome. So make sure your data is decently scrubbed. And if you want to include others in building the list as a way to get them excited before the game, ask each player to submit her own words. But request that the words be unrelated to the usual workplace vernacular. One way to avoid getting the same words (and the same ideas) is to invite players from other areas in the organization, who wouldn’t normally be involved in the brainstorm around the topic you chose. Some of the best ideas come from unexpected places, right?

As the person leading the game, when you announce each random word you may find that you have no idea how to draw representations of them. Draw them anyway. This helps to create a space in which players recognize that their contributions won’t be judged harshly. It matters not only as a basic facilitative technique but also because this game works best when people take risks and post up what can appear to be odd contributions. To encourage bravery, take some risks of your own and be aware that there are certain tendencies the players may have that can stifle the creative process.

For example, after they hear a word, players may attempt to go through a series of steps to relate the word to the product or service: “An airplane reminds me of wind which reminds me of blue which reminds me of the trademark blue of our product.” But there’s no creativity in that – the player’s just retreading an established path. Other tendencies players may have are to rearrange the letters of the word to create another word they associate with the topic or to create an acronym that describes the topic. This is a creative copout. You want people to forge creative, not methodical, paths from the random word to the topic. Sometimes it can be a direct leap; other times it can meander. But encourage them to create anew. Assure them that there are no “left-field” comments and that this play is most effective when people take creative leaps of faith.

If you end up with the opposite challenge – you have a group that jumps right in and starts having crazy fun – let them be energetic but also help them maintain focus on the topic. Give the players enough time to generate lots of ideas but not so much time that they’re no longer connecting the word back to the product/service. With a game this juicy, it can happen.

Note: This game is an adaptation of Edward do Bono’s exercise called ‘Random Input’ from Creativity Workout: 62 Exercises to Unlock Your Most Creative Ideas.

Meeting games

Games are not a new thing at work. In nearly every office environment games are in evidence. Be assured: you are part of a game whether you know it or not. Games are going on all around you and most of the time the rules are unclear, unspoken or unknown.

Whether or not you choose to explicitly bring knowledge games into your workplace, a better understanding of games and game mechanics can help you be happier and more productive at work. We can call this game literacy: An understanding of what games are, how they work, and how they shape our environment.

A game is a socially constructed world where the rules of ordinary life are suspended in favor of a set of rules that the game-players have explicitly or tacitly accepted. Every organization has both written and unwritten rules, and you need to play by both sets of rules if you want to be successful in that organization. The problem with ambiguous or unwritten rules is that people easily become confused, disoriented and sometimes disenfranchised. They check out.

Here are some of the games we have observed in work environments:

I agree with the boss more than you do: Players compete to show the most enthusiasm for the ideas or suggestions of the most powerful person in the room. Moves in this game include loud, conspicuous or unnecessary expressions of agreement or enthusiasm, as well as disparaging comments about alternative positions or perspectives. The winner is the one who curries the most favor with the boss, or gets the boss to appoint him or her to a coveted position or project.

Let’s pretend we all get along: In this game, meetings are somewhat farcical ceremonies where nothing of serious importance is discussed or decided. The real issues are resolved outside the meeting space and the real decision-makers may not even attend the meeting. The meeting leader may be in a position where he or she pretends to have a discussion about a topic, but has no real authority to change anything. Moves in this game can include changing the subject, soft-pedaling difficult questions, and shifting blame to a higher authority or “the system.” The goal of this game is to continue the play without anyone challenging the status quo.

The definition game: Players use language as a game element. The goals of this game can vary widely, from productive to destructive to simply play for the enjoyment of the game. In the definition game, the discussion is paused as players work to find language or semantic issues that can change, derail, or delay the game. One mode of play is to drag the other players into endless discussion and delay the real issues of the meeting. Another mode is where players work to define language such that they can appear to agree when in fact they disagree – a version of “let’s agree to disagree” without making the conflict explicit. This mode is a version of “Let’s all pretend we get along.” The definition game is not always negative. It can be useful when a meeting involves people from different disciplines or different cultures. The goal in that case is to truly understand what is meant by a term that’s in play.

Saboteur: This game is only fun if everybody in the meeting is not in on the game. The goal of the game is to subvert the real meeting in order to nurture a grudge, or for the amusement of the players. Moves in Saboteur are wide and varied. They can be anything from body language, like yawning, crossing the arms and rolling the eyes, to killing any new idea through ridicule or discussing similar ideas that failed. Other moves are pretending you don’t understand in order to impede the meeting’s progress, or taking advantage of a backchannel like Twitter or IM to comment disparagingly on the conversation. A key strategy in Saboteur is to wait until others have staked out a position and then move in for the kill. The goal of Saboteur is to stop or delay any serious progress or change.

King of the hill: Players compete to demonstrate their alpha status within the group. This can be a version of “I agree with the boss more than you do” when players are competing for the boss’s approval, although this is not always the point of “King of the hill.” The goal of this game is to assert your dominance and to get others to show signs of submission. Moves in the game can be anything from an unnecessarily strong handshake to taking the seat at the head of the table.

I’m too busy for this: Players attend a meeting but at the earliest opportunity delve into unrelated work, often by opening their laptops. This is a form of “checking out” but can also be a signal of disinterest or a play for dominance; sometimes it can be a version of “King of the hill.” One very recognizable move in this game is the player who ducks out of the meeting to take an “important call.”

Filibuster: Filibuster is a game about air time. Players angle for center stage and enter into lengthy monologues to promote an agenda or point of view that is only tangentially related to the meeting. Moves may include the introduction of technical jargon to prove one’s expertise, lengthy explanations of unrelated topics, or raising issues from other domains to get them the widest possible audience. Filibuster may also be a play for attention for its own sake. The goal of the game is to keep the center stage for as long as possible.

Here’s why you all should like this: This game is played by authority figures in hierarchical organizations who want to discourage conversation about difficult topics. Decisions are presented to a group and a pretend “discussion” ensues. Controversial decisions are “spun” or presented as “good news” and any discussion of the controversial aspects is discouraged. Moves include “We’ve already discussed that” and body language like that seen in Saboteur. The goal of the game is to maintain the appearance of consensus without changing any of the decisions. One version of this game is “Let’s all agree with me” where a power- player continually raises the same “suggestion” until all disagreement evaporates. One sign that this game may be underway is when managers do most of the talking and frontline workers are noticeably silent.

Sock puppet: Players try to increase their status or the importance of a point by claiming to speak for a constituency that isn’t present. They may represent this point of view as coming from others but more often than not it is their own. Moves include terms like “I’ve heard,” “People are saying” and so on. A key strategy in this game is to refuse to identify one’s sources in order to protect them from retribution. A player wins when the other players agree to the validity of their point.

Shell game: The goal of this game is to postpone meetings and decisions indefinitely. In this game, meetings are moved all over the calendar to accommodate everyone’s schedule, or decisions are postponed because everyone wasn’t able to attend. Difficult topics are “punted” into the next meeting. Players avoid making decisions until everyone agrees, and attempt to keep as many issues unresolved as possible. This can be a version of “Let’s all pretend we get along.”

I’m sure it’s clear by now that these kinds of games go on all the time, in nearly every organization. Players are not even necessarily conscious of their roles as players in a game, and yet they play anyway, sometimes out of boredom and sometimes out of habit. The point here is not that “game-playing” is a negative thing in work environments, but that games are a natural activity; they are part of the social construct and part of how work gets done. And like any other practice, they can be constructive or destructive.

Knowledge games are a way of bringing structure and clarity to the work environment. They make the game – and the rules of the game – explicit, so everybody knows what game they are playing and why. When people understand and agree to the rules, they can put themselves more fully into the game. A knowledge game creates a safe place for people to explore new and sometimes uncomfortable ideas. They are more engaged in their work, they collaborate better, they contribute more, and a better work product is the result.

Why knowledge games work

The way humans gain the lion’s share of what we know is through a slow process of gathering informational knowledge – accumulated layers of additive information based on years of exposure and experience. For example, my knowledge of Spanish is informational knowledge. I learned it through years of listening to Spanish speakers and eventually formalized it by taking multiple semesters at university, building up bits of knowledge to get a fairly complete understanding of the language. And along this learning path, I had an anticipated outcome – fluency. I would eventually know enough verbs, conjugations, vocabulary, etc. to present myself as a Spanish speaker. But nowhere along that learning curve did I create something rather than just accumulate it. Spanish was already there; it was just a matter of me methodically crawling through it, adding to my increasingly large pile of information.

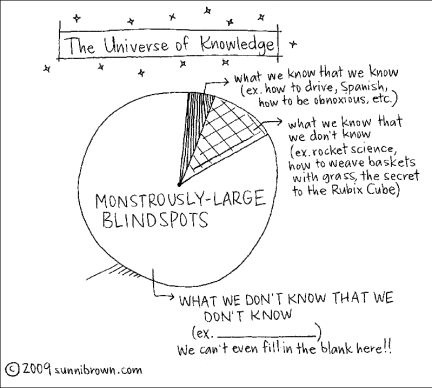

And this is how most of us approach problem-solving – by applying informational knowledge. We think of a problem (or perhaps create one!), get a sense of its magnitude, reference relevant information we know and then apply it as a solution. And there are many situations in which this is a perfectly appropriate plan of attack: you see someone choking in a restaurant, you hurriedly scan your knowledge from the past, you perform the Heimlich. Brilliant. But the shadow side to this type of problem solving is that it confines you to the boundaries of the smaller pieces of the pie chart above – the realm of what you know and the realm of what you know that you don’t know. So if you know the Heimlich (even half-assed), you try it. And if you know that you don’t know the Heimlich, you’re likely going to seek out someone who does and ask them to solve the problem. But it’s highly unlikely that you’re going to spontaneously invent a new move and liberate a choking gentleman from his hambone. That’s just not the way informational knowledge works. And if you impress yourself by actually inventing a new anti-choking technique, well, surprise. You’ve just entered the realm of transformational knowledge.

Transformational knowledge is knowledge that can seem to appear out of the ether. It emerges almost as a flash – a eureka moment – and appears most often when we’re either under duress or in a child-like state of learning. But since most of us eschew being “child-like” – we do take ourselves rather seriously – rarely do we get access to the biggest piece of the pie chart. We spend almost all of our time vacillating between the two dinky realms of either ‘what we know’ or ‘what we know that we don’t know.’ So it’s not shocking that when we’re tackling problems – business or personal – we find our way to the same results. How innovative can we really be when we’re treading and retreading the same ground? But don’t misunderstand; we’re not at fault – we can hardly be held responsible for what we don’t know that we don’t know. But we can be responsible for actively trying to get access to that space. To that big, mysterious piece of the pie that’s hoarding almost all of the creative solutions.

Knowledge games, as set forth in our book, are powerful because they’re designed to help us move out of the familiar and predictable and into the uncertain and unknown – where creation actually lives. We’re including games and meeting processes in which the rules aren’t rigid, you can veer away from a directed outcome and you’ll often be surprised at how it all turns out. We’re giving you tools to create, not repackage. And this is important because, as Einstein understood, “Problems cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them.”

Eureka.

Note: This post was inspired by Landmark Education, a forum that applies the notions of informational vs. transformational knowledge in the areas of human consciousness and performance.What is a knowledge game?

What is a knowledge game?, originally uploaded by dgray_xplane.

Games and play are not the same thing.

Imagine a boy playing with a ball. He kicks the ball against a wall, and the ball bounces back to him. He stops the ball with his foot, and kicks the ball again. By engaging in this kind of play, the boy learns to associate certain movements of his body with the movements of the ball in space. We could call this associative play.

Now imagine that the boy is waiting for a friend. The friend appears, and the two boys begin to walk down a sidewalk together, kicking the ball back and forth as they go. Now the play has gained a social dimension; one boy’s actions suggest a response, and vice versa. You could think of this form of play as a kind of improvised conversation, where the two boys engage each other using the ball as a medium. This kind of play has no clear beginning or end: rather, it flows seamlessly from one state into another. We could call this streaming play.

Now imagine that the boys come to a small park, and that they become bored simply kicking the ball back and forth. One boy says to the other, “Let’s take turns trying to hit that tree. You have to kick the ball from behind this line.” The boy draws a line by dragging his heel through the dirt. “We’ll take turns kicking the ball. Each time you hit the tree you get a point. First one to five wins.” The other boy agrees and they begin to play. Now the play has become a game; a fundamentally different kind of play.

What makes a game different? We can break down this very simple game into some basic components that separate it from other kinds of play.

Game space: To enter into a game is to enter another kind of space, where the rules of ordinary life are temporarily suspended and replaced with the rules of the game space. In effect, a game creates an alternative world, a model world. To enter a game space, the players must agree to abide by the rules of that space, and they must enter willingly. It’s not a game if people are forced to play. This agreement among the players to temporarily suspend reality creates a safe place where the players can engage in behavior that might be risky, uncomfortable or even rude in their normal lives. By agreeing to a set of rules (stay behind the line, take turns kicking the ball, and so on), the two boys enter a shared world. Without that agreement the game would not be possible.

Boundaries: A game has boundaries in time and space. There is a time when a game begins – when the players enter the game space – and a time when they leave the game space, ending the game. The game space can be paused or activated by agreement of the players. We can imagine that the players agree to pause the game for lunch, or so one of them can go to the bathroom. The game will usually have a spatial boundary, outside of which the rules do not apply. Imagine, for example, that spectators gather to observe the kicking contest. It’s easy to see that they could not insert themselves between a player and the tree, or distract the players, without spoiling, or at least, changing, the game.

Rules for interaction: Within the game space, players agree to abide by rules that define the way the game-world operates. The game rules define the constraints of the game space, just as physical laws, like gravity, constrain the real world. According to the rules of the game world, a boy could no more kick the ball from the wrong side of the line than he could make a ball fall up. Of course he could do this, but not without violating the game space – something we call “cheating.”

Artifacts: Most games employ physical artifacts; objects that hold information about the game, either intrinsically or in their position. The ball and the tree in our game are such objects. When the ball hits the tree a point is scored. That’s information. Artifacts can be used to track progress and maintain a picture of the game’s current state. We can easily imagine, for example, that as each point is scored the boys place a stone on the ground, to help them keep track of the score – another kind of information artifact. The players are also artifacts in the sense that their position can hold information about the state of a game. Compare the position of players on a sporting field to the pieces on a chess board.

Goal: Players must have a way to know when the game is over; an end state that they are all striving to attain, that is understood and agreed to by all players. Sometimes a game can be timed, as in many sports, such as football. In our case, a goal is met every time a player hits the tree with the ball, and the game ends when the first player reaches five points.

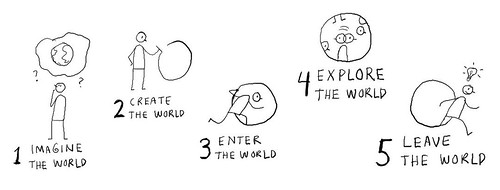

We can find these familiar elements in any game, whether it be chess, tennis, poker or ring-around-the rosie. On reflection, you will see that every game is a world which evolves in stages, as follows: Imagine the world, create the world, enter the world, explore the world, leave the world.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE GAME WORLD

1. Imagine the world. Before the game can begin you must imagine a possible world. The world is a temporary space, within which players can explore any set of ideas or possibilities.

2. Create the world. A game world is formed by giving it boundaries, rules, and artifacts. Boundaries are the spatial and temporal boundaries of the world; its beginning and end, and its edges; Rules are the laws that govern the world; and artifacts are the things that populate the world.

3. Enter the world. A game world can only be entered by agreement among the players. To agree, they must understand the game’s boundaries, rules and artifacts; what they represent, how they operate, and so on.

4. Explore the world. Goals are the animating force that drives exploration; they provide a necessary tension between the initial condition of the world and some desired state. Goals can be defined in advance or by the players within the context of the game. Once players have entered the world they can try to realize their goals within the constraints of the game-world’s system. They can interact with artifacts, test ideas, try out various strategies, and adapt to changing conditions as the game progresses, in their drive to achieve their goals.

5. Leave the world. A game is finished when the game’s goals have been met. Although achieving a goal gives the players a sense of gratification and accomplishment, the goal is not really the point of the game so much as a kind of marker to ceremonially close the game space. The point of the game is the play itself, the exploration of an imaginary space that happens during the play, and the insights that come from that exploration.

Imagine the world, create the world, enter the world, explore the world, and leave the world.

A knowledge game is a game-world created specifically to explore and examine business challenges, to improve collaboration, and generate novel insights about the way the world works and what kinds of possibilities we might find there. Game worlds are alternative realities, parallel universes that we can create and explore, limited only by our imagination. A game can be carefully designed in advance, or put together in an instant, with found materials. A game can take 15 minutes or several days to complete. The number of possible games, like the number of possible worlds, is infinite. By imagining, creating and exploring possible worlds, you open the door to breakthrough thinking and real innovation.

We are writing a book about knowledge games. What games are you practicing in your workplace? What kinds of experiences have you had? Please leave a comment and share them with us!

Comments on “Why games?”

You can read the article here.

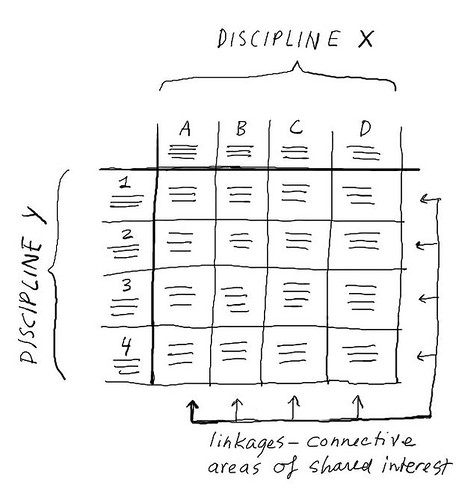

Boundary matrix

Creating a boundary matrix, originally uploaded by dgray_xplane.

Boundary object is a term from sociology used to describe something that helps two disciplines exchange ideas and information, even when their languages and methods may be very different. Today I was in a call with a couple of colleagues, Lou Rosenfeld and Marko Hurst, who were describing a problem that’s very familiar to many of us — the problem of communicating and sharing work between disciplines that are very different. In the case that we were discussing today, one discipline was data analytics, which is very quantitative in nature, very data-driven, in contrast to the other, user experience design, which is primarily quantitative, design-driven. The problem is that the two disciplines think of their work very differently and use different language and tools to approach their work. In a paper titled Languages of Innovation, researchers Alan Blackwell and David Good identify the language problem involved in transferring knowledge from the academic world to industry:

“One might imagine the university as a reservoir of knowledge, perhaps contained within books and the heads of individual academics, from which portions of knowledge can be poured out into the heads of recipients outside the university walls. But which of the available languages might this knowledge be expressed in, and how might it be translated into the languages current in business, industry, government and public service each of which have their own lingua franca? Scholarship does not exist in any form independent of language, so the transfer of scholarly knowledge either takes place in the disciplinary language in which it was formulated, or must be translated.”

This is the challenge many organizations have in conveying information between disciplines, and Blackwell and Good have some very constructive insights in their paper, which I encourage you to read. The ideas in that paper, and the subsequent conversation with two colleagues about some very real problems they were having translating information between “data people” and “design people” resulted in the idea of the boundary matrix. Here’s how it works:

1. First, identify what information needs to be exchanged between the disciplines:

(a) determine what kinds of questions discipline X must ask to get relevant and meaningful information from discipline Y, and

(b) determine what kind of form the answer to the question from discipline X might take, if answered by someone from discipline Y. This could be a document or artifact that is ready and available, or it might involve terms that are specific to discipline Y. For example, a designer who wanted to understand user behavior might need to ask for search terms and click-through rates.

(c) repeat the above from the perspective of discipline Y.

2. From examining these exchanges you should be able to create two lists, one for discipline X and one for discipline Y. Each list element contains a brief description of the discipline-specific term and why it should be important to the other discipline. For example user behavior > search terms, click-through rates.

In the sketch above, these descriptions are labeled A, B, C, D for discipline X and 1, 2, 3, 4 for discipline Y.

3. Now look at your matrix and see if you can find how each cell relates to an area of strategic interest for your company or team. These interior cells represent the points where the disciplines intersect with larger areas of shared interest. If you can’t find the strategic connection that might indicate that the activity might have outlived its usefulness or could be of dubious value to the organization.

The completed chart is your boundary matrix — a “cheat sheet” for managers as well as people from disciplines X and Y, that will allow them to communicate more effectively and quickly navigate to areas of strategic priority or shared interest. This is a new idea and has yet to be tested but I think it holds real promise.

I suspect that the initial value to cross-disciplinary teams will be the conversations it forces about what each discipline does and why it is important to the other discipline, or the organization as a whole. The conversations themselves are an education and culture-building process that will lead to better collaboration, and the better those conversations, the better the boundary matrix that will result.