Object of Play: Co-create products or services using design insights gained from collaborative analysis of key frames of peoples’ activities from video clips recorded during ethnographic field work.

Number of Players: 6 – 12

Duration of Play: 7 – 8 hours

Required Resources: The Video Card Family Game requires use of a video camera (perhaps a smartphone), video editing software, graphics software, desktop publishing software, index card printing stock paper, and a printer (preferably color).

Preparing to Play: The Video Card Family Game is a research technique useful in promoting collaboration among design team members and people engaged in the front-end design process. It uses video recording as a visualization resource for ethnographic fieldwork, especially participant observation among stakeholders (typically a product innovation team) and people who will use the product or service. The preparation time depends on the nature of the project as well as the logistics of the field work.

Ethnographic field work, in the simplest terms, means going to where the people of interest gather to share in their experience and analyze it. Designers use participant observation to co-create insights for product and service design by experiencing the peoples’ activities involved, such as working in their own context, or staging an environment in which people perform the activities of interest using mock-ups or prototypes.

1. To prepare for the Video Card Family Game, the facilitator edits the video into segments of no more than two minutes each. The importance of participant observation comes into play during the selection of video segments. Participant observers select video segments using insights about what is significant that they gained during the field work.

Note: It is important to select video segments in which actions, rather than conversations, are primarily occurring. You want, predominantly, to see what people do rather than hear what they say they do. In other words, focus on video where people are involved in physical action.

2. Save each video segment with a unique file name.

3. Select a key frame from each video segment and give it a unique identifier.

4. Create a video card by copying the key frame for each segment and pasting it into two corresponding index cards in your stock paper template. Give both cards the same title. Number both cards with the same unique identifier. Leave a comment area either below, or beside, the picture depending on how you layout the index cards.

Note: The image from the key frame may need resizing in a graphics editor before pasting it onto the index card stock paper template. You paste the image on two index cards to produce duplicate video cards.

5. Print the duplicate video cards and place each in a separate stack.

6. Repeat steps 2-5 for each video segment.

Note: The number of video cards created from the two-minute segments provides a degree of objectivity in the selection process. Ideally, each game player receives a stack of 10 video cards.

How to Play:

(Allocate one hour for Steps 1 – 5 of playing the game)

1. Explain the rules of the game by providing a synopsis of steps 2 – 10 in the game play.

2. Provide players with instructional guidance on the difference between observing action in video and interpreting action.

Note: Observations come from descriptions of who is engaged in the action, what they are doing, where they are doing it, when they do it, and how they do. Interpretations involve assertions about why particular people do what they do when and where they do it. At times though, how they do it applies to interpretation when it relates to why the action occurs.

3. Group the players into pairs and provide each group with duplicate stacks of video cards.

4. Play the video segments corresponding to each video card in the duplicate stacks provided to each pair of players.

Note: Instruct the game players in each group to review the video segments in their group but not to discuss them with their partner.

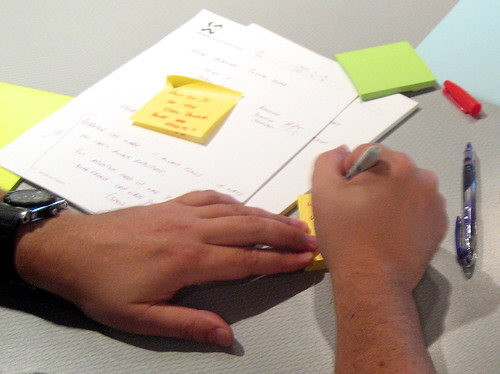

5. Ask players in each group to take observational notes regarding what happens in the video segment corresponding to a video card. The idea here is for each player to personalize their video cards through writing notes on them, making them tangible research artifacts to handle and use in design discussions.

(Allocate 30 minutes for Step 6)

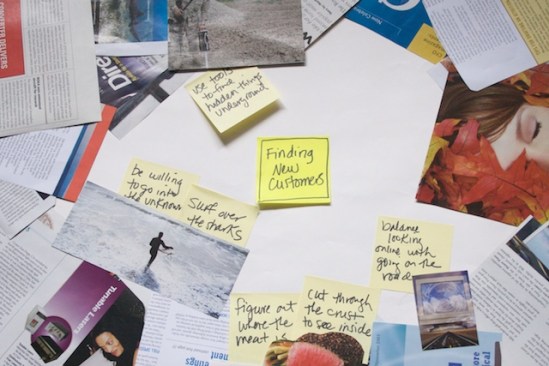

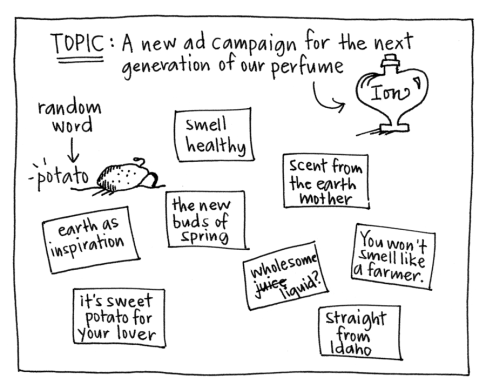

6. Ask each pair of players to discuss what they saw in the video segments and arrange their video cards into “families” that share a theme, before placing them on a table. Any theme is appropriate as long as it makes sense for the design focus of the game.

(Allow 1 hour for Steps 7 – 8 )

7. Ask each player to choose a favorite “family” of video cards from those they identified with the other player in their group. Doing so makes that player responsible for relating the design focus to user input as exhibited in the resulting “family” of video cards.

8. Attach each favorite “family” of video cards to a poster and write a heading for the theme it represents. Organize the video segments corresponding to each “family” for easy review.

(Allow 3 – 4 hours for Step 9)

9. Bring all the players from all the pair groups back together with their posters. Ask each player to describe and show their favorite “family” of video cards and invite other players who think their video cards fit, or resemble, the theme to add them to that family.

Note: The game property of the play comes to bear at this step, since the idea of the game is to pass as many cards from your stack to others as possible. The player describing their favorite “family” attempts to avoid further additions to their theme by playing the relevant video segment and explaining why the proposal to add another video card does not fit. No single player has seen all the video segments. Therefore, accepting or rejecting a video card for each theme depends on all the players reviewing the video segment from which the video card proposed for addition is drawn.

(Allow 1 hour for Step 10)

10. Document the themes by having members of each group write a structured description using the following format:

- Describe the theme

- Describe why it belongs in the family you assigned it to

- Provide at least two examples

- Describe the way the action occurs in context

- Describe the way people employ the action in the context

Strategy

Video of people’s activity is one of the most challenging resources used in design research. Playing and replaying video segments for review is time consuming and, depending on the number of people involved and the type of activity recorded, difficult to distill into agreed upon insights. The Video Card Game’s design provides a collaborative structure for interaction between designers and users to co-create insights for product and service design from video sources.

When playing the Video Card Family Game, facilitators need to remember that, even though the video cards give the video a tangible mode of expression, the images remain on relatively small cards, whether on the surface of a table or attached to a poster on the wall. One can imagine an interactive wall display like Microsoft’s Surface that minimizes the legibility problem. Short of such a solution however it is important to keep in mind the logistical limitations imposed by rendering video representations of action onto video cards.

Provenance

The Video Card Family Game draws from the “Happy Families” children’s card game, a game in which players collect families of four cards as they ask one another in turn for cards of a particular archetype. The goal of “Happy Families” is to collect a family of four cards, forming a stack. Collecting the most stacks makes you the winner.

Werner Sperschneider, a user-centered designer, at the Danish industrial manufacturer, Danfoss A/S, created the initial version of the Video Card Game as a method for combining ethnographic and visual research methods using video. Design researchers, Margot Brereton, Jared Donovan, Stephen Viller, at the University of Queensland, as well as Jacob Buur and Astrid Soendergaard, of the University of Southern Denmark, and the University of Aarhus, respectively, also provide case studies of its use.

The rendition of the game offered here refers to it as the Video Card Family Game for the explicit purpose of making it clear that Ludwig Wittgenstein’s concept of family resemblance is a key criteria in the gaming process for deciding to which themes a video card belongs.

Larry Irons is a Principal at Customer Clues, LLC. Larry practices Experience Design — translating strategic business goals, and the complex needs of people, into exceptional experiences for those who provide products and services, and those who consume them, whether the latter are customers, users, learners, or just plain people. He writes the blog, Skilful Minds, which blogs.com listed as one of the top ten Customer Experience blogs in 2009. Skilful Minds is also listed in the top 99 Workplace eLearning blogs by eLearning Technology.